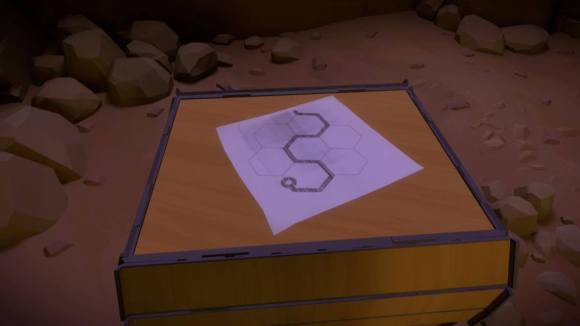

First off, what is The Witness? At its core, The Witness is a puzzle game. Players walk out of a tunnel on an island where they are immediately tasked with solving puzzles that become increasingly more difficult. The base idea of the puzzles is to draw a line from a starting point to an end point. But anyone who has spent a significant amount of time with the game knows that most of the puzzles are anything but simple.

My analysis of this text reminded me a lot of Kelly Gallagher’s Model for the Teaching of Challenging Texts. Gallagher’s model is broken into the following elements: framing the text, read carefully, return to the text, collaboration, and a metaphorical or reflective response. As you work through these steps, you move from a surface level of understanding to a deeper understanding of the text.

I bring up this model because it aligns well with my process of play with The Witness. Many times during my playthrough I felt as though the game was treating me as a student so using this model for analysis (as a student on the receiving end of a text presented by video game developers) makes sense to me.

Framing the text. One of the first things that caught my attention with The Witness was the lack of direction or purpose. Many open world games afford similar kinds of freedom as this game, but something was different. I walked out of the tunnel at the start of the game and started solving puzzles because…I was supposed to? The Witness doesn’t really inspire much in players initially. I had to put my faith in the game and that it would eventually lead me to something meaningful. I understand that Jonathan Blow doesn’t believe in coddling players, but there is a significant difference between coddling and throwing players into a world without further instruction. Quite often video games have a narrative structure which provides a framework or tricks players into creating their own framework–which is what The Witness expects you to do.

Essentially The Witness asks players to solve puzzles just to solve puzzles. This is its frame. I think. Perhaps my uncertaintly lies in the fact that the puzzles are set in such a convincing world that the puzzles seemingly can’t be everything. In fact, the puzzles, and how they are placed in the world, are highly suggestive that there is more to the island than drawing lines.

When you clear a section of the island, a laser points toward the mountain. And on top of the mountain there are a number of statues depicting humans in various acts and poses. The Witness leads players on suggesting that there may be a mystery. After all, the island is empty of human and animal life, but at the same time, there are numerous man-made buildings and structures. Clearly someone lived here at some point but now they are gone without a trace. The island’s very design, its absences, encourages the player’s mind to fill in the gaps. My mind instinctively went to “solve a mystery!” Perhaps the inhabitants were murdered. Were they destroyed by some disaster? Who made the puzzles? Why am I here. Who am I?

Typically games are framed through their tutorial sections or levels. However a game may attempt framing (giving players a purpose), the first few moments of gameplay are crucial. The Witness may be a bit too open in this regard and suffers from a lack of direction.

Read carefully. As I walked across the island, I could not simply solve puzzles. I began to question why I was solving puzzles and what they were hinting to if anything. I questioned why I could see my avatar and why that avatar was male (I believe I can safely claim this without much debate). A faceless avatar strips identity away and allows virtually any player to accept that avatar as him or herself, but I wanted to know who he was. As soon as a gender is assigned, half the population is excluded. This gendered choice imposes an aspect of identity onto players and is one aspect I have come to question.

But gender is only one facet of The Witness that I began to “read,” or analyze, carefully. The more puzzles I solved, the more I realized their relationship to the surrounding world. Some puzzles require players to stand at particular angles to solve them or to be highly observant of the environment immediately around the puzzle. In fact, one such environmental puzzle can be solved within the first few minutes of playing the game and leads to one of the three endings. However, this relationship between puzzle and world only furthered my thought that the puzzles were left behind by the island’s inhabitants and that those inhabitants were trying to tell me something.

I searched the proverbial nooks and crannies and found nothing. I turned to the statues around the island searching for answers. My hopes that they would tell me anything were quickly dashed. I could not find any connections between the statues besides their empty faces and grey exteriors. I was left feeling a little more than perturbed.

Return to the text. I took a step back from the game and returned with a relaxed mind. I really tried to focus on what the text was telling me by doing what it wanted me to do. I solved puzzles left and right, lasers started shooting from all over the island, and I discovered more and more of the audio logs. The more puzzles I solved the more determined I was to complete the game even if the game told me nothing more than it had a few hours ago.

Collaboration. After what felt like an eternity of playing and finding few answers to my questions of purpose and motivation, I turned to the internet (hah). Since the game failed to keep me motivated, I read through a few reviews and articles offering praise and was encouraged to keep going by their observations and perspectives. It’s popularity among average players (just check out the Steam reviews) also motivated me to stick with it and plough ahead. So I did till the bitter endgame…

Reflective Response. Ultimately I reached the standard endgame and was left feeling defeated and confused. I’m not sure I can tell you what the game’s central theme is. Discovery? Epiphany? I approached the game in earnest knowing very little about Jonathon Blow or his previous game–I had no reason for bias.

To be clear, it’s not the game’s puzzles that confuse me but the game’s abstractions. As an avid video game player and reader, I am used to picking apart dense ideas, but I just don’t buy into the idea that The Witness is that great. It’s beautiful and different, but I didn’t find it profound. My experiences are my own and that makes them subjective.

While I have only played through two of the game’s endings, I am aware of the third. I have read articles where the claim is made that it is easy to miss the hidden secrets of The Witness. I can accept that; however, if a game fails to motivate players to keep playing, to keep inquiring, it fails at some point to adequately hint toward those secrets and rewards. Quite honestly, the major “revelation” of one of the endings was not that impressive. Maybe I was expecting too much, but the revelation did not elicit a “woah” moment for me.

And yes, I understand that The Witness expects more of its players on an intellectual level than some, perhaps most, games, but I am not the only one commenting on the lack of purpose with the game. This absence is partly tied to motivation. Essentially The Witness asks players to solve puzzles just to solve puzzles. There is no major revelation at the endgame. Instead, players find that they start at the beginning. Back in that dark tunnel, I questioned what I was missing because surely I had missed something. It was me and not the game. Right?

I felt as though the game was messing with me. Players walk through a tunnel and into the light, but what are players walking into? I expected a mystery because of the design choices made by the developers. Or, at the very least, I anticipated some form of thinly traced narrative. The only narrative I experienced was my own (not that there is anything inherently wrong with that). Players form their own narratives every time they pick up a controller or place their hands on wasd. The game certainly challenged some of the expectations I held regarding video games. I ended up reflecting on my expectations and on the ways video games have shaped my thinking–which is valuable.

The “failings” of this game remind me a lot of the struggles of teaching. It can be difficult to engage students in subject matter especially if that subject rests beyond their field of comfort, familiarity, or expectation. Educators must conduct a balancing act of challenging students without pushing them too far into frustration. The value of learning and inquiry is subjective to each individual, but educators can set up lessons and texts in ways that establish purpose and meaning.

Many successful video games also have goals and purposes that reinforce why players play. Abstractions are fine but can require guidance. Reaching an endgame to discover that the beginning was the end or that the whole thing was a “dream” is cliche at this point and does little to impress me. What saddens me is that I learned very little. This is not to say The Witness does not have meaning for other players or that it is incapable of teaching you something. My experience with the game differs from many, but I don’t think being an outlier makes my experience irrelevant.

The Witness and its developers never claimed to offer any truth, even if the game’s design is suggestive of a mystery and unanswered questions. The game potentially takes players on a journey of discovery where simplicity is paradox and enlightenment is an enigma. But these “revelations” seem minor in light of the game’s whole.

I can’t tell you definitively what The Witness‘ purpose is or what I witnessed, but I can tell you that I struggled with it, and I’m not all that sure that struggle was necessarily fruitful or futile. Really the only satisfaction I felt was retiring the game to my completed catalog.