I lived here until I was eleven but I wasn’t allowed inside half the rooms.

What Remains of Edith Finch (WRoEF) is a narrative experience, what some would call a walking simulator, focusing on family, childhood, death, and grief. What follows is less of a review and more of my thoughts on what makes WRoEF successful and unique among games focusing primarily on such narrative experiences.

But instead of a family, there were just memories of one.

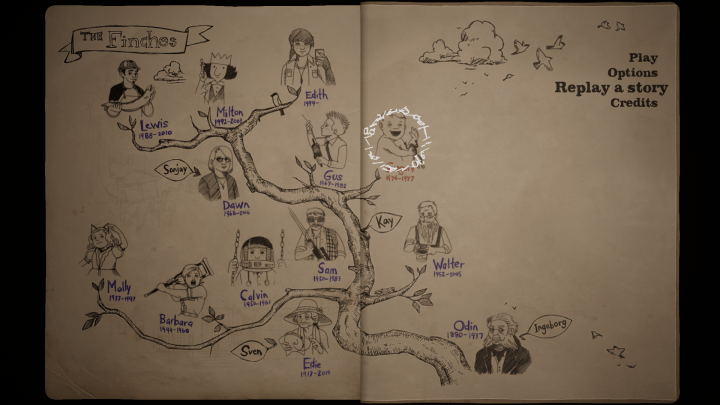

The number one element that makes WRoEF successful is that it keeps players motivated through suspense and inquiry. The game begins with Edith returning to her childhood home, a hodgepodge of rooms, tunnels, and stairways. She has returned to Washington state to fill in the blanks of her family history; this sense of not knowing gives players an immediate reason for action—get in the house and start digging.

As a kid I just assumed every house had peepholes and sealed rooms you weren’t allowed inside of.

The opening bits of dialogue contribute to this suspense by shaping the situation that Edith is in while relaying clues and setting the tone for the player. It helps that the voice acting for the game is solid and relatively genuine in its performance. Edith always managed to say just enough to keep me wondering.

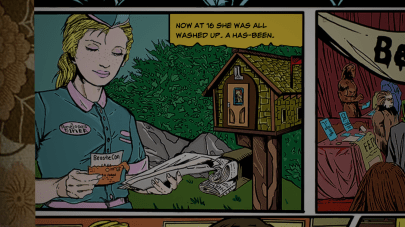

Whenever people ask me about my family, the first thing they always want to know about is Barbara.

Along with the dialogue, the environment of the house and the surrounding area builds a mysterious aura. One of my gaming pet peeves is when a game presents itself in a cryptic or scary way, usually in terms of the atmosphere/environment, but it is nothing more than a cheap move at making the game seem more than it is. I was not mislead with WRoEF. The game certainly exudes a sense that the house and the Finch family have their secrets, but it’s not going to pull a cheap jump scare when that’s not what the game is about.

Each of the Finch family members has a story to tell. The house displays scenes and moments of their happiness, but quite often, that joy is overwhelmed by loss and sadness. The tonality of these emotions is what is displayed in the environment and not a sense of terror.

It is a depressing game at times but also one where I found moments that spoke to me. All of us have experienced loss in some form or other in life, and the observations of the characters involved reminded me of both the laborious and triumphant moments we can experience. Sometimes we are the fear that is holding back what could be.

Beyond the narrative, what I really enjoyed about the game is that it didn’t rely solely on dialogue and diary entries to tell the Finch’s stories. Each room/story involved a mini sequence with varying levels of player involvement to advance the current story (Edith’s overarching tale is shaped by these vignettes). These sequences are at their best when they require heavy interaction from the player. One of my favorite stories was Barbara’s which lead players through a comic book. Players have to move Barbara through some of the panels to progress her story which seemed like a clever addition to the game.

I enjoyed the few hours I spent with What Remains of Edith Finch and believe it is one of the more successful narrative-based games. I really do hate the term “walking simulator” because its use is often derogatory. However, if I had to call WRoEF a walking simulator, I would say that it is one of the more interactive and unique ones due to how it is broken down into individual stories and how each story plays out. While brief, WRoEF made for an enjoyable morning of gaming.

For educator’s, I can see WRoEF as a potential text for the classroom. It deals with mature themes, it is relatively cheap, and because the game offers a tight narrative experience, you can’t go in many directions or deviate too far from the path, it can be played in two or three hours. It is also a game I would feel relatively fine about having students play on their own time since it is not overly complicated in terms of its mechanics and control scheme. The individual rooms/stories could also act as natural stopping points for discussion as well (I could see assigning two or three stories at a time and dividing them among class periods).